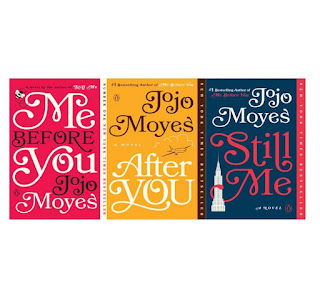

Me Before You a Book Review

Book One - Me Before You

I don’t like doing negative reviews but I can only give my opinion.

In the first few chapters of listening to this, I, as a disabled person who needs help and assistance, was saddened and offended by the assumptions and low expectations people have of disability.

The story follows Will, a thrill seeking adventurer, whose motorbike accident causes him to lose the use of his legs and have limited arm movement. Will sinks into depression.

Lou has lost her job at a cafe and applies to be Wills companion.

A few chapters in, I began to like Will and Lou’s banter, but still the secondary family characters annoyed me with their judgement that wheelchair/mobility aid = no life, and that the disabled person is stuck, staring out of the window all day, with nothing to look forward to. This preconceived notion is wrong and sadly JoJo Moyes affirms this.

Another judgement is the fear ables have that the disabled will be 'head lolling' and unable to communicate. This got me wondering, is this really what people think or is it just the author and her own ignorant attitude?

After Will’s accident, his friends abandon him. Two, including girlfriend, Alicia, only visit Will twice in a year. I'm sure Will did push her away, and, indeed, people - friends, family- do run in fear, but a few do stick around. I don't see why Will couldn't have used voice activation light switches, computers and tablets. This would've given him so much more independence.

Disabled people are allowed to go out (I know shocking right🤣). I understand that the first time of using your mobility aid can be daunting, but eventually you have to do it. How can you meet people, gain new experiences, otherwise?

As it becomes clear how the book will end, it raises the questions of, is there enough support emotionally for disabled people (answer: no) and also about assisted suicide.

Lou cooks up a plan to try and change depressed Will, who hasn't left the house since his accident two years ago, other than for hospital appointments. Will it be enough?

Words like 'revulsion' as Will met with old work colleagues, enduring their pity and looks of relief that they had escaped his fate made me sad. Do people really feel this fear of us?

I found Will’s comparison of his chair to a glorified pram quite offensive. Is this why people talk through or down to me? Do they think I’m a 33 year old baby? The characters reluctance to see his own potential was very disheartening. It upset me to hear him say the only place disabled people can live is in their memories of when they were fully able, what must he think of those born disabled?

What this book does highlight is just how inaccessible the UK is. This bit I could relate to (Lou makes a list of 15 places that are accessible, which is rather depressing). Yes, there are lots of historic buildings with steps and yes, travel needs planning, but there are ways round it, such as: the London Underground doesn't always have a lift, so try the bus!

Will’s self pity became annoying. I, of all people, know how hard disabilities are too accept, but there comes a point when you have to try - look for support, see what equipment is out there, get counselling... Disability doesn't mean your life is over, it’s just different.

I may have been a bit harsh in this review, but I have found it to be incredibly ableist, stereotypical with the 'being disabled is awful' rhetoric and the terrible judgements people made of Will, without even knowing him. As I have said, these assumptions enraged me and made me think, do people really think this??

As Lou spends so much time with Will, she develops feelings for him. Of course, in this ableist story, other people are shocked - how can she, a fully able woman, see beyond his wheelchair, and see Will as funny, intelligent and handsome? The viewpoint that disabled people can't possibly be attractive or feel attraction to others is a totally misguided one!

As Will makes his decision, slating his situation, hating his wheelchair, missing his old life, I felt anger surge through me. How dare this able author equate a disabled life to ‘regretful' and unworthy? Yes, there are days when I wish I could wave a magic wand, have eyes that see, ears that hear, hands not twisted in pain, a mouth that speaks and is heard, understood, legs that walk, but I can't alter my health. I can, however, use technology to help me. I can ask for support, join groups. I can see that my life is worth living. I am valued.

At the end of the book, there was an interview with the author, in which, she described a rugby player who became paralysed and died at Dignitas and a relative who moved into a care home and JoJo knows that if they could, ‘they wouldn’t be here'.

I have heard that none of the disabled community were consulted. I have also tweeted Moyes to ask what research she did for it, but, as yet, no answer. This is an appalling, ableist book whose theme should be of acceptance, instead the message is: disability = no life.

No wonder many of the disabled community do not like it, it slides into the Victorian mantra of pity, judge, hide. I have my own views on assisted suicide that I won’t share here. This review is just about the way the attitudes in the book made me feel.

I began this book in an effort to cheer myself up when feeling down. I did not find it life affirming or in any way positive about disability and do not recommend it.

This book is so full of inaccuracies that if I listed them, it'd be longer than this review!

Book Two - After You

Lou is now working in an airport bar. Dealing with grief, she has an accident and falls off a roof. At this point, I had thought she'd end up paralysed (worst fear for an able person, apparently). As Lou recovers she questions her life, but soon returns to it.

One night, a teenage girl knocks at her door, could Lily really be who she claims?

What the second instalment shows is the effects of grief. Will has died. Lou is struggling to cope. Can the revelation of Lily transform her life as much as Will did? Can Lily save Lou in return?

The ableist misconceptions continue, although to a lesser degree. This time it was that wheelchair = confinement. It took me a long time to accept my chair and see it as a key to freedom. This book has so much potential to change opinions, to see the positive of disability, instead, it does harm, feeding into a notion that wheelchair users all depend on others, that our mobility aids hinder us, rather than give us the opportunity to enjoy life. Did Moyes even talk to disabled people or did she assume everyone thought like Will (the character she created) and took away the chance for true representation!

A theme of this book is that of sexism and Lou’s mother's reaction to the patriarchal hierarchy. In her rebellion, her mum Josie, stops cooking the dinner, shaving her legs and cleaning the house in an effort to teach her husband responsibility. This is fine, but surely the writer and her publisher have a responsibility to the disabled community? Or do they think we don't read? I am always interested in books with disabled characters, to see how the author, especially a non disabled author, portrays us, but this again alienated me.

Book two is less about Lou and about Lily finding herself. As a protagonist, Lou doesn't really develop. The pace of book two is much slower than the first, there are fewer laugh out loud moments, perhaps because Lou is grieving, this was more about the relationships Lou has. Towards the end, a hint of book three is given.

Book Three - Still Me

The final book takes Lou to the Big Apple, where she is, again, working as a companion. This time, to Agnes, the wife of a multi millionaire American man. Lou has to navigate the cold housekeeper, Agnes’ stuck up stepdaughter and a manic new routine.

When Lou meets Josh at a New York charity ball, there’s an instant attraction. Josh reminds Lou of Will (in his looks and confident, self assured manner. Josh is not disabled). Can she stay faithful to Sam, her sweet boyfriend back home in London?

A theme of this book is mental illness, in the form of depression. Agnes' moods are erratic. It's an interesting topic, but like with Will’s physical disability, I don't feel it’s been handled well - the character is isolated by her situation, throws things around in frustration, like a tantrumming toddler, has a few low moments in between many highs. Although I don't have personal experience of bipolar or multiple personality disorder, I have studied mental illnesses and this is what it sounds like, not depression.

As Lou discovers a secret about Agnes, her circumstances change and Lou learns who her New York friends are. Can Lou trust Josh? Just because he has a similarity to Will, doesn't mean he is Will. The blurb mentions that Josh reminds Lou of Will. Perhaps presumptuous of me, but I thought this meant he was disabled. I made this assumption based on how judgemental and anti disability I felt the author was. I’d hoped this would show disability in a positive light. But no, the only hint of disability was Agnes' mental health crisis.

The main themes in this book are love, loss and finding yourself, not letting others dictate or change you. Of the three, I enjoyed this one the most. The story, although somewhat predictable, it did have some funny moments and more interesting characters than the others, but purely for the insulting, ableist content in book one, I won't be reading any more of JoJo Moyes’ books.

When I began these, I thought they’d be life affirming, uplifting, cheer me up when I felt down.... I was wrong. The language used is harmful. I see attitudes like this kind on a day-to-day basis. Perhaps they have all read Me Before You and are repulsed by people like me, perhaps they too think I am unable to communicate, perhaps they define me by my wheelchair and blind cane.

Books that represent a portion of society that the author is not part of need to be thoroughly researched. Readers, who, in this case, are not disabled, will assume this is how we all think. When, in fact, disabled people are just as sociable, adventurous and ambitious as the able.

Another issue raised is that of carers/paid companions/p.a/ support workers. It is unlikely that a disabled person would be able to afford: private healthcare, a 24/7 physio nurse, a total home adaptation renovation or a top of the range adapted car. Will had no waiting lists, no medication refusals and a fantastic holiday with no airport mishaps.

I’ve found that there are two reactions to people in the care sector.

They are:

1. A snobbishness, as portrayed in Me Before You, when Lou’s sister looks down on her for 'wiping bums all day'. This simply isn't true. Yes, some may need personal care, but not all. Many, myself included, just need assistance to live an independent life. It’s going out, travelling, just having someone to talk to. To look down on someone enabling a person to be independent, is low.

The other option comes across as quite patronising to both the disabled person and the p.a:

2. People revere the p.a and ignore the person they are with. I once went to a disability group with my p.a. A man said to her, 'you're a hero, looking after people like her.' I am sure he meant well, but we both cringed.

Disabled people are among the most vulnerable and often poorest in society. Businesses that sell equipment hike up the prices, others think we should have our mobility cars taken away. What the non disabled don't see is, the constant struggle. The fight for access, social care, health care, education, medication, housing, transport, medical understanding, just understanding for people to see that you are a person too. You have goals, dreams, ambitions too. It's a fight to be seen or heard. Being disabled is a fight to just survive.

A message to authors: remember, you have a responsibility to those you write about. Your words will change opinions. Make sure it’s for good, not harm.

Comments

Post a Comment